Sargassum spp. (Phylum: Ochrophyta, Class: Phaeophyceae): Elemental analysis and spatial distribution approximation

Sargassum spp. (Phylum: Ochrophyta, Clase: Phaeophyceae): Análisis elemental y una aproximación a la distribución espacial

María Teresa de Jesús Rodríguez Salazar1*, José Luz González Chávez1, Caterin Gutiérrez Sánchez2, Analaura Skladal Méndez2, Ariana Janai Morales Velázquez2, Esperanza Elizabeth Mendoza Solís2, Rafael Ibarra Contreras2, Norma Ruth López Santiago1

1 Departamento de Química Analítica, Facultad de Química, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Cd. Universitaria, CDMX, México, CP 04510.

2Facultad de Química, UNAM.

Email: mtjrs@quimica.unam.mx/mtjrs.papime2020@gmail.com

Rodríguez Salazar, M.T.J., J.L. González Chávez, C. Gutiérrez Sánchez, A. Skladal Méndez, A.J. Morales Velázquez, E.E. Mendoza Solís, R. Ibarra Contreras & N.R. López Santiago. 2025. Sargassum spp. (Phylum: Ochrophyta, Class: Phaeophyceae): Elemental analysis and spatial distribution approximation (Review). Cymbella 11(1): 63-87.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/fc.24488100e.2025.11.1.3

Abstract

This review for the 1984-2023 period, includes a sampling sites information employing the Google Earth platform: https://earth.google.com/earth/d/1Qd72z9YXRpNVqmv5jqqJQftJlfS4JLgS?usp=sharing. The seaweed species mainly analyzed were: Sargassum polycistum, S. wightii, S. fluitans, S. natans, and S. muticum. The most common chemical analytes determined were: Cu, Mn, Zn (micromineral), Ca, K, Fe, Mg, Na, P (macromineral), As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb (PTE), C, H, N, S, O (organic elemental analysis). There were a few isotopic data for 210Po and 210Pb (radioactive) and 13C and 15N (light stable). The contamination risk evaluation was preliminary estimated through the indexes CF, Cd, PLI, Eri, and PERI using As, Pb, Cd, and Zn global reported concentration data for Mexico´s sampling sites and guideline limits available. In Europe there is regulation for macroalgae but not yet in Mexico. The preliminary indexes values obtained are higher considering the European Regulation is more severe than the Mexican Standards not specific to the use of biomass (NOM 187, NOM 242, and NOM 247). Thus, the analyzed Sargassum spp. seaweed could be classified as “high” risk for As and Cd content, and “moderate” for Pb and Zn.

Key words: Chemical composition, contamination risk evaluation, Sargassum, spatial distribution.Resumen

El presente trabajo de revisión para el período 1984-2023, incluye la información de los sitios de muestreo utilizando la plataforma Google Earth: https://earth.google.com/earth/d/1Qd72z9YXRpNVqmv5jqqJQftJlfS4JLgS?usp=sharing. Las especies de macroalgas más analizadas son: Sargassum polycistum, S. wightii, S. fluitans, S. natans y S. muticum. Los analitos mayoritariamente determinados son: Cu, Mn, Zn (microminerales), Ca, K, Fe, Mg, Na, P (macrominerales), As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb (PTE), C, H, N, S, O (análisis elemental orgánico). Se reportan datos isotópicos: 210Po y 210Pb (radiactivos) y 13C y 15N (ligeramente estables). La evaluación del riesgo de contaminación se estimó preliminarmente a través de los índices CF, Cd, PLI, Eri, y PERI utilizando datos globales reportados en sitios de muestreo de México para el contenido de As, Pb, Cd y Zn, y los valores permisibles disponibles. En Europa sí existe regulación para el consumo de macroalgas, pero no en México. Los valores preliminares obtenidos para los índices son mayores para la Regulación Europea que las Normas Mexicanas existentes NOM 187, NOM 242 y NOM 247 (no específicas para el uso de la biomasa). Las especies de la macroalga Sargassum spp. analizadas podrían clasificarse como riesgo “alto” para los contenidos de metaloides como As y Cd, y “moderado” para los metales Pb y Zn.

Palabras clave: Composición química, evaluación del riesgo de contaminación, sargazo, distribución espacial.Abstract Abbreviations: S.: Sargassum; CF: Contamination Factor; Eri: Individual Potential Risk Factor; NOM 187: NOM-187-SSA1/SCFI-2002 Standard; PTE: Potentially Toxic Elements; Cd: Degree of Contamination; PERI: Total Ecological Risk Index; PLI: Pollution Load Index; NOM 242: NOM 242-SSA1-2009 Standard; NOM 247: NOM-247-SSA1-2008 Standard.

INTRODUCTION

The origin and location of the tropical floating Sargassum spp. are related to the North-Equatorial Recirculation Region (NEER), the Sargasso Sea (place with greatest abundance of pelagic species), and the main currents in the Central Atlantic (Baker et al. 2018; DCNA 2019; Fernández et al. 2017; Hinds et al. 2016). The Langmuir Ocean Circulations allow the grouping of the macroalgae mats (Baker et al. 2018; Barstow 1983) as the case of the macroalgae arrivals to the Mexican Caribbean coasts. INECC (2021) reported the abundance of the Sargassum natans and S. fluitans at the coast, as an environmental problem (related to tourism, economic and health sector) due to a combination of eutrophication from human pollution and oceanographic conditions changes (as temperature).

Sargassum spp. (brown macroalgae) is classified according to Puspita (2017) in Phylum: Ochrophyta, Class: Phaeophyceae, Order: Fucales, Family: Sargassaceae. Hinds et al. (2016) highlight the ecological value of floating seaweed as a habitat, shelter, and food for many marine species. Fleurence & Levine (2016) report the potential applications of documented marine macroalgae in the world. For example, a) Years 13000 B.C. for nutrition and health in Chile country, b) Years 0 – 300 A.C. for medicinal use in Greece, as fertilizer in Rome, and as food supplement in Japan. Other reported applications point towards pharmacology and cosmetics of various bioactive compounds of Sargassum spp. (Hinds et al. 2016; Puspita 2017), biogas (Hernández López 2014; Hinds et al. 2016), hydrocarbon pollution bioindicators of petroleum (Lourenço et al. 2019), heavy metal biosorbent in contaminated water (DCNA 2019; Hinds et al. 2016), pest control, feed supplements, fish and livestock feed, agglomerated material for construction (Hinds et al. 2016). Milledge & Harvey (2016) highlight the therapeutic use of bioactive compounds in diabetes, cancer, AIDS, vascular diseases, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory treatments. Rushdi et al. (2020) look over the reported bioactive compounds and the biological activities for clinical applications of Sargassum species from the Red Sea.

Diverse methods and techniques have been used to analyze the chemical composition of Sargassum samples collected in multiple geographical locations, including volumetry, colorimetry, potentiometry, gravimetry, atomic and molecular spectrometry, and chromatography (Addico & deGraft-Johnson 2016; Baker et al. 2018; Fernández et al. 2017; Hernández López 2014; Lourenço 2019; Puspita 2017; Rohani-Ghadlkolact & Abdulalian 2012; Solarin et al. 2014). Several investigations (Addico & deGraft-Johnson 2016; Fernández et al. 2017; Hernández López 2014; Lourenço 2019; Milledge & Harvey 2016; Puspita 2017; Rohani Ghadlkolact & Abdulalian 2012; Solarin et al. 2014) provide data on the chemical composition determined: a) As, Cd, Cu, Cu, Mo, Ni, Pb, Se, Zn, Be, Cr, Co, Hg, Na, K, Mg, Ca, Ag, Al. B, Bi, Cs, Fe, Ga, Ge, In, Cl, Mn, P, B; b) Rare earths: Ce, Dy, Er, Eu, Gd, Ho, La, Lu, Nd, Pr, Sc, Sm, Tb, Tm, Y, Yb; c) Nitrate and phosphate anions; d) C, H, O, N, S; e) Proteins, lipids, polyphenols, carbohydrates, pigments, polycyclic aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons; f) Percentage (%) of Organic matter, and total ash. Solarin et al. (2014) mention that AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists) methods to analyze the samples were used.

This paper aims to present a map review with the chemical composition (elements, isotopic analysis, not speciation studies) reported in Sargassum spp. samples, and data analysis of recent years (2019-2023), specifying the information reported from studies in Mexico (1995-2022). Also, the global data was evaluated concerning to As, Cd, Pb, and Zn guideline limits from regulation available, using the preliminary estimation of the indexes Metal Pollution Index (MPI), Contamination Factor (CF), Degree of Contamination (Cd), Pollution Load Index (PLI), Individual Potential Risk Factor (Eri) and Total Ecological Risk Index (Eri or PERI). This document attempts to contribute as a tool for the integral management (collection, analysis, application, and disposal) of Sargassum seaweed as a raw material, knowing the main inorganic content data reported.

METHODOLOGY

The specialized documentary research was carried out by using the www.bidi.unam.mx platform, the National Autonomous University of Mexico Digital Library (DGB 2023), getting eighty-six references covering the period 1984-2023, highlighting: a) Ten articles from the Journal of Applied Phycology, b) Six publications from the Science of the Total Environment Journal, c) Four papers from the Algal Research Journal and the same founds from Marine Pollution Bulletin. The main database was ScienceDirect, except for the Journal of Applied Phycology. Three doctoral and four master's theses were also recopilated.RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sargassum species and mostly elemental analytes determined.

During 2020 and 2021 an Excel database (two files) that can be seen in the AMyD (Rodríguez Salazar et al. 2023; SPI 2023) free website from Facultad de Química, UNAM was elaborated (https://amyd.quimica.unam.mx/course/view.php?id=662§ion=5). Figure 1a shows that Asia leads the research about Sargassum spp. marine macroalgae, with 45% of the chemical composition references found; the second place corresponds to 27% for America; next, 17% for Europe; and, finally, 11% corresponding to Africa. The Sargassum spp. species reported are shown in Figure 1b. The most studied corresponds to S. fluitans and S. natans in America, S. muticum in Europe, S. polycistum and S. wightii in Asia, and S. elegans in Africa. There was also found research in Africa for the Sargassum spp. composed of S. fluitans and S. natans.

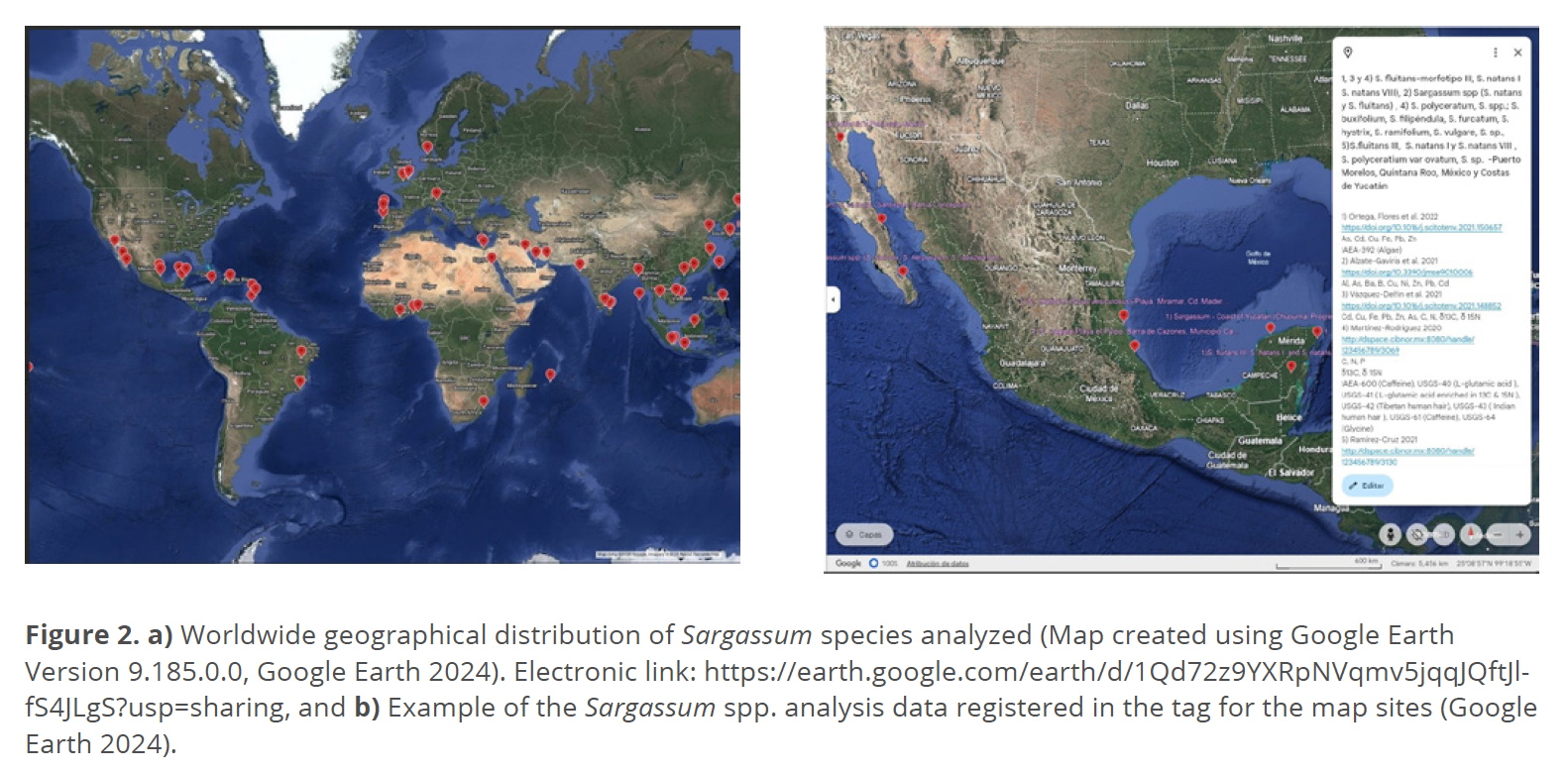

With the above database information mentioned, and updated references during 1984-2023 period, there were mapped (Figure 2a) the sampling sites employing the platform Google Earth Version 9.185.0.0 (Google Earth 2024), with the next electronic link allowing the visualization

https://earth.google.com/earth/d/1Qd72z9YXRpNVqmv5jqqJQftJlfS4JLgS?usp=sharing (free website). Figure 2b displays the content registered for each point mapped: a) Sampling site (the cited references contain the precise geographical coordinates from the sampling location), b) Analytes, c) DOI (Digital Object Identifier); and d) Certified Reference Material (CRM), if it was used for the analytical methodology as quality assurance.

In Figure 3a, it is observed that most determined analytes by the called group are:

a) Organic elemental analysis: C, H, N, S, O.

b) Potentially toxic elements (PTE): As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb.

c) Macromineral elements: Ca, K, Fe, Mg, Na, P.

d) Micromineral elements: Cu, Mn, Zn.

e) Special isotopic analysis: 210Po and 210Pb (radioactive) in Sargassum boveanum and Sargassum oligocystum from Kuwait (Uddin et al. 2019), 13C and 15N (light stable isotopes) in S. fluitans and S. natans from Mexico (Martínez-Rodríguez 2020; Vázquez-Delfín et al. 2021). Figure 3b displays the preliminary concentration average and maximum concentration levels found. According to the average concentration values (mg/kg) the lowest are for Cd, Ni, and Pb; while the highest are for K, Na, and C.

Table 1 specifies information about recent research published corresponding to the 2019-2023 period, which contains the Sargassum species analyzed, the sampling site, an analytical technique for the elements determined, and the main findings of the reported results for the authors of the reference cited. The highlighted location of several Sargassum species can be observed:

a) Africa: Sargassum obovatum, S. cf. portierianum, S. robillard, S. pfeifferae, S. elegans, S. vulgare, S. cinereum (Bekah et al. 2023; Madkour et al. 2019; Magura et al. 2019; Mahmoud et al. 2019).

b) Iberian Peninsula: S. muticum (Álvarez-Viñas et al. 2019; Rodrigues et al. 2019; Torres et al. 2021).

c) Caribbean: S. fluitans, S. natans, S. polyceratium (Alzate-Gaviria et al. 2021; Davis et al. 2021; Gobert et al. 2022; Martínez-Rodríguez 2020; Ortega-Flores et al. 2022; Ramírez-Cruz 2021; Rodríguez-Martínez et al. 2020; Thompson et al. 2020; Vázquez-Delfín et al. 2021) and also S. vulgare (Martínez-Rodríguez 2020).

d) Asia: S. horneri (Huang et al. 2022; Tamura et al. 2022), S. fusiforme (Huang et al. 2022; Su et al. 2021), S. wightii (Ajith et al. 2019; Thadhani et al. 2019; Yoganandham et al. 2019), S. polycystum (Corales-Ultra et al. 2019; Sumandiarsa et al. 2020; Thadhani et al. 2019), S. ilicifolium (Kordjazi et al. 2019; Siddique et al. 2022).

To determine the analyte´s concentration level, the most employed analytical techniques, according to Table 1 were:

a) Organic Elemental Analyzer (OEA) by combustion using infrared detectors and thermal conductivity for quantification of C, H, N, S (and oxygen by difference).

b) Inductively Coupled Plasma- Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) for PTE.

c) Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS), Inductively Coupled Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES) for macromineral and micromineral elements, and also ICP-MS for elements at trace concentration levels.

d) Specific volumetric method to determine nitrogen (Kjeldahl) and Ultraviolet-Visible Spectrophotometry for phosphorous.

e) Special isotopic analysis as Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) to determine 13C and 15N, and Alpha Spectrometry (AS) for 210Po and 210Pb (radioactive).

f) Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) to determine arsenic.

Among the overall findings obtained through the Sargassum spp. sample analysis were as a natural source of bioactive compounds such as vitamins (A, C, B complex), polyphenols, polysaccharides (fucoidan, alginic acid), functional metabolites (alanine, guanidinoacetate, ethylene glycol), fatty acids (palmitic acid, oleic acid), phytosterols (b-sitosterol, fucosterol), phaeophytin and minerals nutrients as Mg, Ca, K, P, N, Fe, Mn, Zn (Álvarez-Viñas et al. 2019; Alzate-Gaviria et al. 2021; Bekah et al. 2023; Choi et al. 2020; Circuncisão et al. 2018; Dewi et al. 2019; Kordjazi et al. 2019; Magura et al. 2019; Rodrigues et al. 2019; Sumandiarsa et al. 2020; Tamura et al. 2022; Torres et al. 2021; Thadhani et al. 2019; Yoganandham et al. 2019).

According to the valuable chemical composition of the seaweed, the potential applications studied reported were: a) Environmental: production of bioethanol and bioplastics, carbon capture, bioaccumulation of heavy metals (Ni, Cu, Pb), arsenic remover, pollution biomonitoring, bioremediation for polluted water and soil, b) Biomedical: antioxidant activity and action against cancer, antidiabetic treatment, nutraceutical products, antihypertensive properties, c) Agro-Food Industry: alginate extract, fertilizer, natural plant growth stimulant, ruminant feed (Ajith et al. 2019; Álvarez-Viñas et al. 2019; Choi et al. 2020; Corales-Ultra et al. 2019; Davis et al. 2021; Delgadillo Mendoza 2022; Dewi et al. 2019; Gouvêa et al. 2020; Gutiérrez Sánchez 2023; Huang et al. 2022; Kordjazi et al. 2019; Leyvas Acosta et al. 2023; Madkour et al. 2019; Mahmoud et al. 2019; Rakib et al. 2021; Ramírez-Cruz 2021; Sumandiarsa et al. 2020; Tamura et al. 2022; Thadhani et al. 2019; Torres et al. 2021; Yoganandham et al. 2019).

This research paper details information reported for Mexico’s Sargassum spp. sampling sites in Table 2. The data registered are Sargassum species analyzed, sampling site, analytes (including isotopic data), and concentration level (keeping the unities reported for the authors). The sampling sites correspond to Mexico´s Caribbean and Gulf and Baja California Peninsula. The main species reported are S. fluitans and S. natans for the Caribbean and S. sinicola for the BC Peninsula. On the whole, it can be observed the concentration level for the elements determined in the real samples (Fig. 3b): a) Trace: Al, As, Cd, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb, Zn, b) Minor: Fe, N, P, and c) Major: C, Ca, K, Mg, Na. About the isotopes 13C and 15N, the numerical value indicates an enrichment or depletion of the heavier isotope (13C, 15N) relative to the lighter (12C, 14N). Through the isotopic characterization, the next findings were observed: the pelagic Sargassum species acquire carbon as HCO3- and are associated with the biological fixation of atmospheric nitrogen (Martínez Rodríguez 2020).

Preliminary estimation of the contamination risk evaluation, through available regulation.

Related to the previous overall findings paragraph, Table 3 presents Mexican regulation data available that may be useful to take advantage of the Sargassum spp. as a natural resource and not as a growing pollution problem. The allowance concentration levels for As, Ba, Be, Ca, Cd, Cr, Cu, F, Fe, Hg, I, Mg, Mn, N, Ni, P, Pb, Se, Sn, Tl, V, Zn, and also Ag (not analyzed yet in the reported studies of this review) are recommended by the Official Mexican Standards (NOM). The NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010 (SE & SSA 2010), NOM-247-SSA1-2008 (SSA 2009), NOM 242-SSA1-2009 (SSA 2010), and NOM-187-SSA1/SCFI-2002 (SSA & SE 2003) are employed for Foodstuff applications. While for soil use the norms are NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (SEMARNAT 2002), NOM-147-SEMARNAT/SSA1-2004 (SEMARNAT & SS 2007), and NOM-004-SEMARNAT-2002 (SEMARNAT 2003). The NOM-127-SSA1-2021 (SS 2022) supplies the radioactivity specifications for drinking water (alpha 0.5 Bq/L, beta 1 Bq/L).

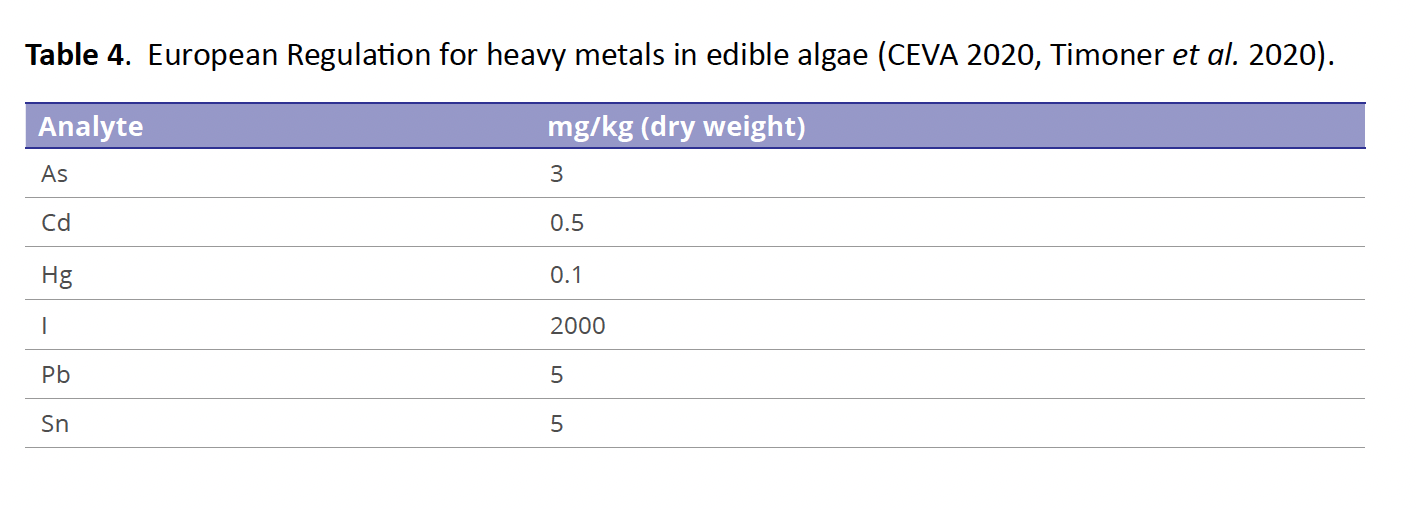

Data from Table 2, were evaluated for possible pollution risks and contamination degree, using different indexes taking into account as background concentration values the guideline limits established by the regulation available (in mg/kg) for PTE (As, Cd, Pb) by the European Regulation shown in Table 4 (CEVA 2020; Timoner et al. 2020) and by the mentioned above Mexican Standards (NOM 242 for fishery products, NOM 187 for corn products and NOM 247 for other cereal products). The essential element Zn is regulated by NOM 247. The European Commission is applied to edible algae consumed in the continent for example, the called Hiziki (S. fusiforme).

The MPI (Rahhou et al. 2023; Rajaram et al. 2020; Rakib et al. 2021;) to evaluate the pollution between species, was applied only as an example for S. fluitans y S. natans data from Ortega Flores et al. (2022) and Vázquez Delfín et al. (2021), because both studies determined the concentration for the five elements mentioned above. The MPI calculated using the maximum concentration values were: 1) Based on PTE and Zn: 3.7 and 30.5 for VD and OF, respectively, and 2) Based only on PTE: 2.9 and 23.9 (VD and OF, respectively). The data from Ortega Flores et al. (2022) represents a major source for elements evaluated.

Using the average values, the indexes CF and PLI (reported by Shams El-Din et al. 2014; Tyovenda et al. 2019) were calculated for seaweeds as bioindicators due to potential bioaccumulation for heavy metals (and also Zheng et al. 2023 for mangrove ecosystems). Other indexes were calculated in analogy for the Sargassum spp. samples: Cd, Eri, and PERI (described by Alkan et al. 2020; Hankanson 1980; Mahammad Diganta et al. 2023), using the average and maximum concentration data reported.

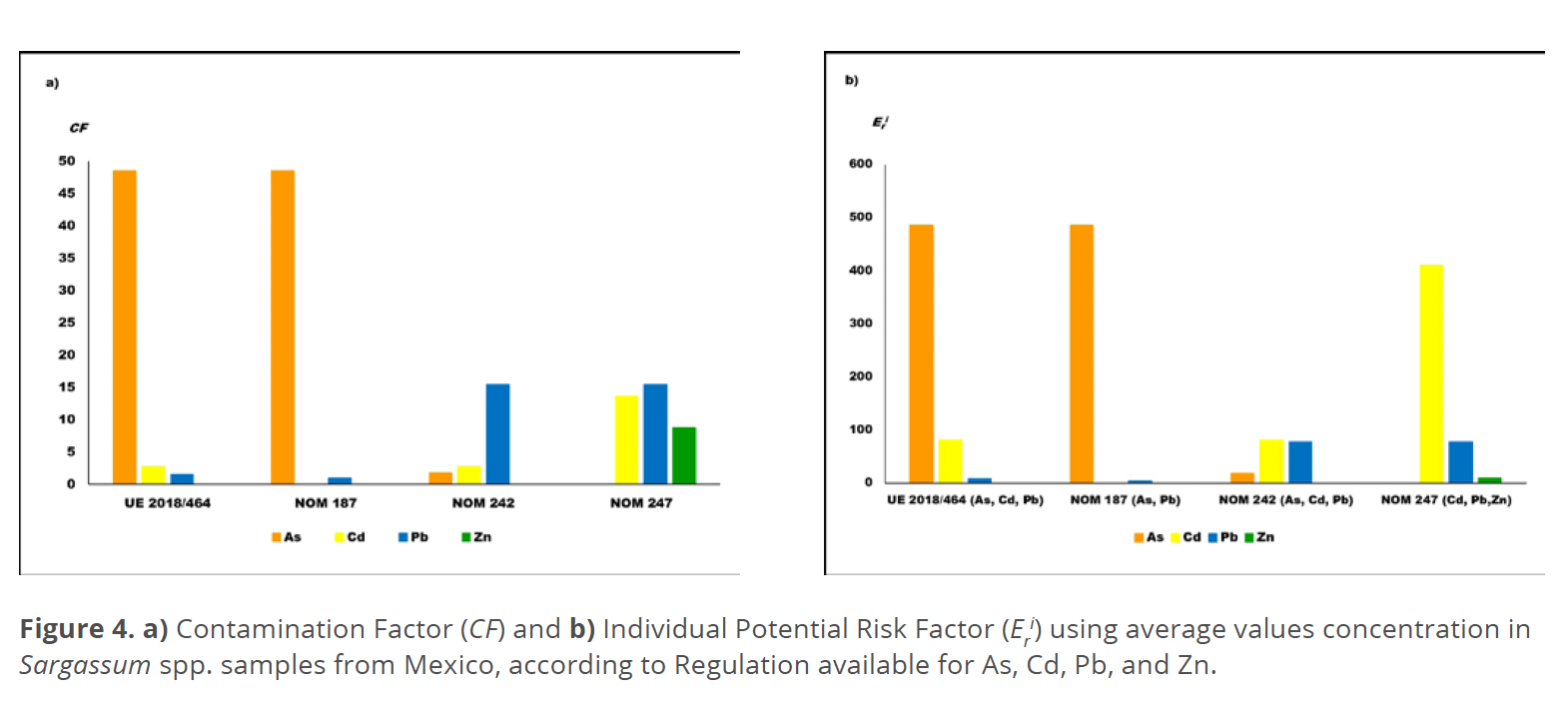

The results for CF and Eri calculated are presented in Figure 4a and 4b, where it can be seen that the European Regulation and NOM 187 establish more severe guideline limits than the other Mexican standards mentioned previously. The PTE As and Cd contribute in a high degree to the index value, exceeding the limits. In accordance with indexes scale values (Alkan et al. 2020; Karimian et al. 2021; Mahammad Diganta et al. 2023; Tyovenda et al. 2019), the contamination level could be classified as “high” with respect to As and Cd, and “moderated” for Pb and Zn content, using the global data reported for Sargassum spp. macroalgae evaluated from Table 3. But if NOM 242 and 247 are applied as criteria for Pb, then it surpasses the guideline values. The micronutrient Zn does not represent ecological risk according to the NOM 247 standard, because the Eri has the value <40 (Karimian et al. 2021; Mahammad Diganta et al. 2023).

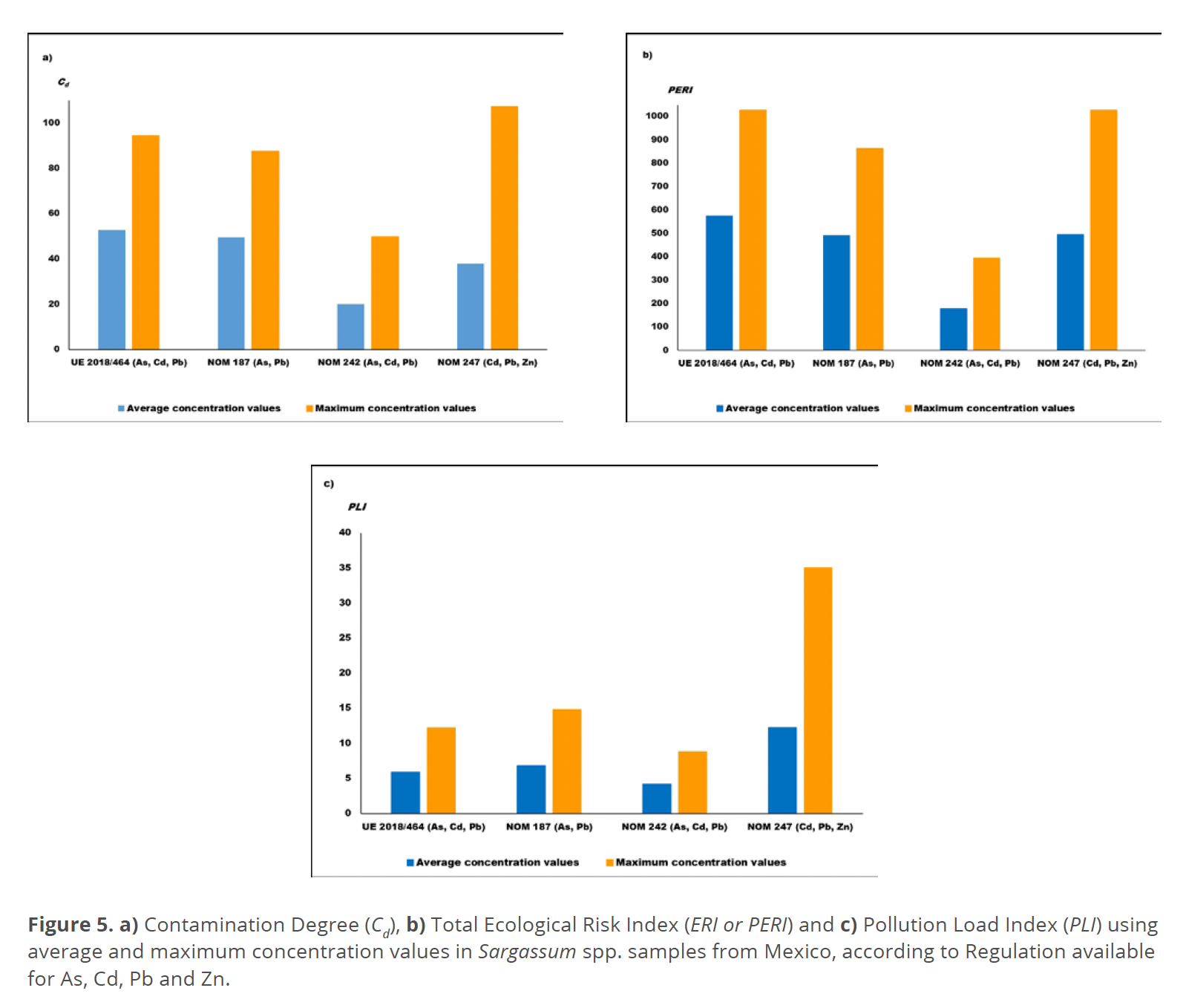

Figures 5a, 5b, and 5c displayed the Cd, PERI, and PLI, considering the global data reported for As, Cd, Pb, and Zn. The graphs show the higher index values calculated using maximum concentration values found than the index values obtained with the average concentrations. In general, the Cd and PERI diagrams show the next descendent order in calculated indexes values with respect to the standards criteria for guideline limits: European Regulation > NOM 187 > NOM 247 > NOM 242 (Fishery Products). While for PLI values the order was: NOM 247 > NOM 187 > European Regulation > NOM 242.

The indexes scale values available (Alkan et al. 2020; Håkanson 1980; Karimian et al. 2021; Mahammad et al. 2023; Shams El-Din 2014; Zheng 2023) were used also to evaluate the possible contamination risk from the content of PTE (As, Cd, Pb) and Zn, identifying the “moderate” classification of the organisms according to the less severe NOM 242 for Fishery products, and “high” contamination risk applying the European Regulation (macroalgae consumption) and Mexican Standards NOM 187 and 247 (Corn and Cereal Products), especially concern to As and Cd. This paper advises about the contamination risk, instead of polluted in agreement with the definition of both terms given by Chapman (2007), considering that the index values calculation is based on concentration levels and their dispersion, the elements included, and the guideline limits criteria.

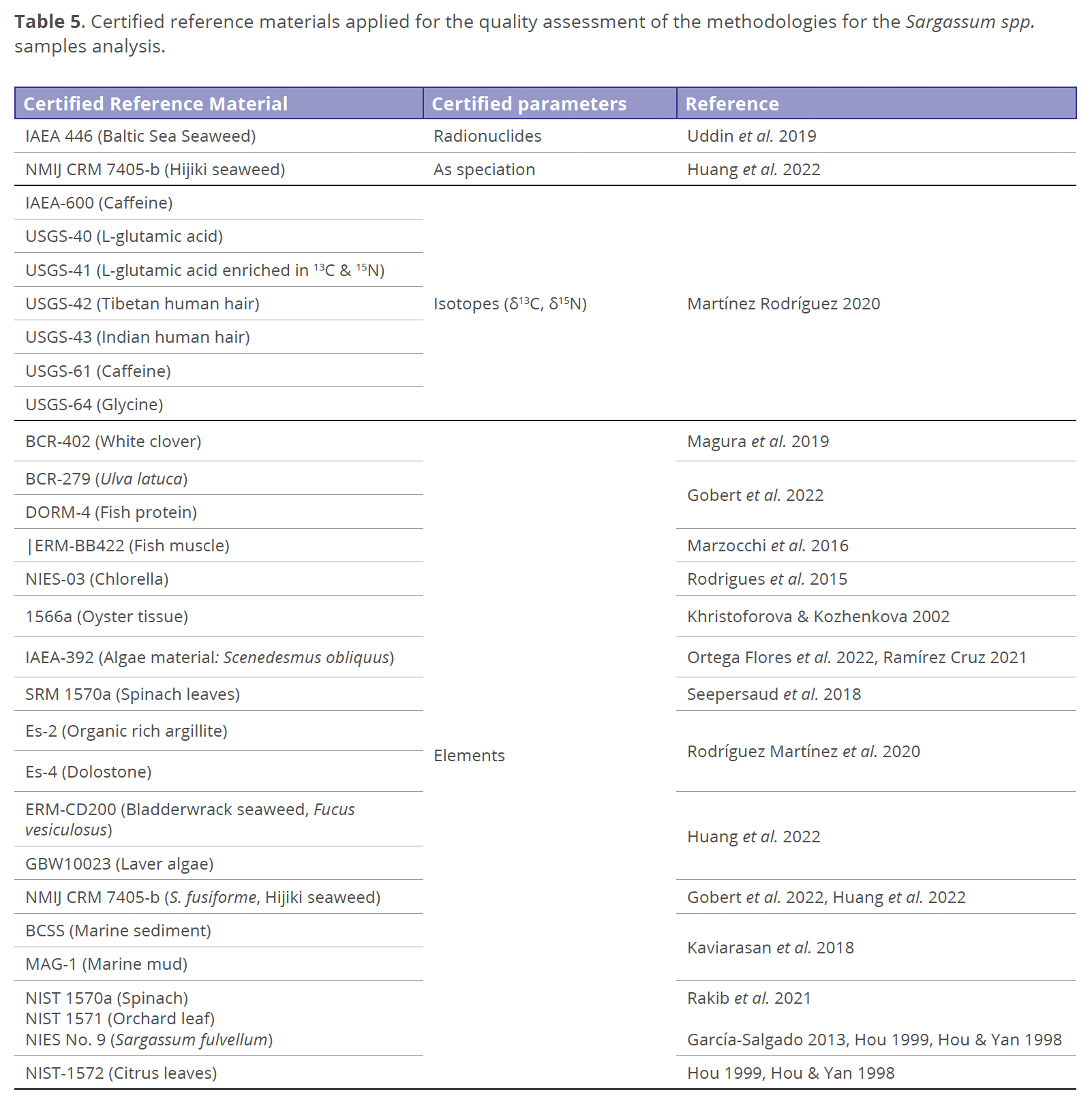

This review also remarks that the data about the analytical quality assurance are not ordinarily reported. Table 5 displays the certified reference material (CRM) for analytical methodology validation applied to the macroalgae analysis reported in this review. The CRM based on seaweed matrix are for elemental analysis: BCR-279 (Ulva lactuca, not yet available), NIES-03 (microalgae Chlorella spp.), ERM-CD200 (Bladderwrack seaweed, Fucus vesiculosus), GBW10023 (Laver algae) NMIJ CRM 7405-b (S. fusiforme, also for arsenic speciation), NIES No. 9 (Sargassum fulvellum). The CRM IAEA 446 (Baltic Sea Seaweed) was applied for radionuclides analytical methodology. For isotopic analysis, the sample matrix types are, for instance, caffeine (IAEA-600, USGS-61) and human hair (USGS-42, USGS-43), and there is no reported seaweed matrix yet. This review agrees with the observation about the opportunity area to characterize the Sargassum species to know the chemical constituents and its properties associated with benefits that could be obtained from this biomass instead of considering it as a waste. And advice about the requirement to evaluate environmental indexes and establish regulation about the well-known chemical species with human and animal health risks previous to the application of the macroalgae (like a raw material). And also considering the effects of heavy metals in morphology, growth, photosynthesis and metabolic process on seaweeds, a was documented by Chung & Lee (1989).

Complementary environmental findings. The research about Sargassum spp. seaweed draws attention to its properties as a call to take advantage of the observed following information:

Inorganic components.

The data obtained by Madkour et al. (2019) indicated the accumulation of Fe, Mn, and Zn in the studied macroalgae species; hence, they can be used as a good target for monitoring metal pollution in marine waters.

Corales-Ultra et al. (2019) found that S. polycystum bioaccumulates heavy metals, following the metal uptake descending order: Ni »Cu > Pb.

Siddique et al. (2022) reported overall mean values <1 for Hazard Index (HI) for metals (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, Ni, Mn, Cr, Fe) and Hazard Quotient (HQ) for bioaccumulation of carcinogenic elements (Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni).

Low total concentration levels of Cu, Mo, Zn, Mn, and Pb were found by Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2020). However high total concentration levels found for As exceeded the allowable limits; and the availability for application as animal fodder and agricultural soil according to European regulations can be restricted.

Thompson et al. (2020) reported that high Hg and As content could limit the exploitation of Sargassum species as biogas. Through the hydrothermal pretreatment of the biomass, it was possible to reduce the H2S concentration from 3 to 1% in the biogas obtained.

Differences in arsenic concentration (μg / g as dry weight, dw) levels between the coastal and oceanic area Sargassum species collected were observed experimentally by Gobert et al. (2022): 30–45 and 120–240. The above is because of the depuration performed by the competitive exchange with high concentrations of terrigenous metals (Al, Fe, Mn) in the coast.

Inorganic arsenic (iAs: AsIII + AsV) analysis was also performed by Huang et al. (2022) reported a high iAs concentration of 15.1 to 83.7 mg/kg, especially in S. hemiphyllumand S. henslowianum. These values exceed the limit for seaweed as additives for infant food in the National Food Safety Standard of Pollutants in China. The authors also evaluate the water extraction efficiency for As species, obtaining values above 60 %.

Rakib et al. (2021) evaluate Pb content in S. oligocystum, where the concentration level (10.63 mg/kg), exceeds the maximum international guidance level (5 mg/kg) recommended by the French High Council for Public Health and The Center for the Study and Development of Algae (CEVA), and as leafy vegetable according to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 0.3 mg/kg).

Martínez-Rodríguez (2020) evaluates the carbon and nitrogen biological fixation by the macroalgae using C and N isotopes. The numerical values foundwere δ (o/oo)13C -18.26 ± 0.40 in S. fluitans III and 15N -1.03 ± 0.73 in S. natans I.

Radioactive isotopes were found by Uddin et al. (2019) for S. boveanum and S. oligocystum, the Concentration Factor values observed were:

a) 210Po (•104): 1.05 and 0.85, respectively for both species. These values are higher than the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) recommended value (1 •103).

b) 210Pb (•103): 0.8 and 1.54, respectively. Both values are below the ICRP (International Commission on Radiological Protection) recommended value (2 •103).

Dewi et al. (2019) produced an organic liquid fertilizer from Sargassum sp., through the addition of a bread starter with Saccharomyces cerevisiae microorganism to accelerate the fermentation process (transforming glucose into ethanol, CO2, and organic acid as pyruvic acid and lactic acid). Some chemical parameters of the product were evaluated: 2.7 % N, pH 5.43, and 94.36 % total solid content. The tempe starter addition with Rhizopus oligosporus microorganism gave a high content of micronutrients such as Fe, Mn, and Zn.

Organic components.

Davis et al. (2021) found that S. fluitans and S. natans pelagic morphotypes (I and VIII) are carbohydrate sources for microbial production of ethanol and bioplastics.

Magura et al. (2019) reported that S. elegans macroalgae contains bioactive compounds: β-sitosterol, fucosterol, and phaeophytin.

Choi et al. (2020) performed the identification and quantification of functional metabolites in S. fulvellum useful for rumen fermentation, among them: alanine (1.00 ± 0.06 mM/L), guanidoacetate (41.93 ± 3.36 mM/L) and ethylene glycol (8.21 ± 0.69 mM/L). The study also found high content of: a) minerals (Na and Ca) with nutritional value, b) As (122.05 ± 5.69 mg/kg), and c) F (4.37 ± 0.18 mg/kg). The arsenic concentration is within the acceptable limit for ruminants’ feed.

Mahmoud et al. (2019) applied an extract from S. vulgare to red radish plants as a natural plant growth stimulant. The results showed significant improvement in the next parameters: plant length, number of leaves, the diameter of roots, and leaf pigment content (chlorophyll a, b, a + b, and carotenoids). Also, similar effects were observed for increasing the nutritional content: a) Phytochemicals compounds (total phenolics, flavonoids, and anthocyanins), and b) N, P, K, Fe, Zn, and Mn.

Tamura et al. (2022) confirmed the arsenic removal and the antihypertensive effect of fermented pretreatment of S. horneri with Lactiplantibacillus pentosus SN001, enhanced ACE (angiotensin-I-converting enzyme) inhibitory activity. The above was done by analyzing the liver, kidney, and spleen of the spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) model.

Rodrigues et al. (2019) performed an enzymatic aqueous extraction with Alcalase for S. muticum to concentrate macro and microelements, increasing the nutritional values for K and P. Also, it was confirmed the presence of polysaccharides as fucoidans with prebiotic and antidiabetic potential. And no cytotoxicity against normal mammalian cells was observed.

Torres et al. (2021) obtained an ultrasound-assisted hydrolysis of crude fucoidan from S. muticum, and it was observed cell growth inhibitory activity against human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa 229).

Álvarez-Viñas et al. (2019) as a result of fractionation of fucoidans obtained from Sargassum by hydrolysis treatment through a sequence of progressively lowering molecular weight membranes (different Kilodalton values, kDa), observed the next:

c) 10–30 kDa: fraction showed IC50 (concentration inhibiting growth by 50 %) 44.4 mg L, against cervix cancer cells (HeLa 229).

d) 50–100, 5–10, and < 5 kDa: fractions found active against ovarian cancer cells (A2780).

There have been carried out estimations of the above-ground biomass (AGB), which represents an ecological practical parameter to study the carbon cycle taking into account the function of the forests in carbon storage and climate change (Li et al. 2023). Gouvêa et al. (2020) obtained the next information as a combination of predictors to the distribution for Sargassum species (floating and benthic):

a) Iron, temperature, salinity, and phosphate: 305.95•104 km2 Pelagic (floating).

b) Light at the bottom, nitrate, salinity, and temperature: 139.59•104 km2 (benthic).

For both species, it was obtained a total area of 445.54•104 km2, 84.05 Gg/km2 value for AGB, and predicted 13.1 Pg C (petagrams of carbon per year) value for carbon stock in AGB globally. These authors point out that “…Sargassum aquaculture, natural stock management, and restoration can represent important allies in the urgent need for CO2 mitigation…”.

CONCLUSIONS

A map with the sampling site of reported studies was developed using the Google Earth platform and it could be seen that most of the research has been conducted in Asia, analyzing mainly S. polycistum and S. wightii species, followed by America with S. fluitans and S. natans (for example at Mexican Caribbean).

Through the review data on chemical composition (elements and isotopic, not speciation) was observed that most of the determined analytes correspond to Potentially toxic elements (As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb), macromineral (major) elements (Ca, K, Mg, Na) and micromineral (trace) elements (Cu, Mn, Zn); from the human health approach. According to the concentration level of the above elements, analytical techniques such as ICP-MS (trace), ICP-AES (minor and major), and the AAS methods (Flame, Graphite Furnace, and Hydride Generation) were employed. Stable and radioactive isotopic analysis were also found to be scarce: a) 13C, 15N in Mexico, and b) 210Po and 210Pb in Kuwait. The appropriate quality assurance approach to worldwide analysis results necessary. The use of available CRM reported for algae matrix: NIES-03, ERM-CD200, GBW10023, NMIJ CRM 7405-b, and NIES No. 9 is recommended.

The preliminary estimation for CF, Cd, PLI, Eri and PERI indexes allows to advise about a “moderated” to “high” risk contamination due to the As, Cd, Pb and Zn concentration global data reported for the Sargassum spp. samples analyzed at Mexico sites, especially when it follows severe guideline limits as European Regulation or Mexican NOM 187 or NOM 247. Although this is in agreement with that, the biomass is viable as a biomonitoring and bioremediation material.

Nowadays, in Mexico there is no specific regulation for the emerging exploitation of Sargassum spp. biomass, although it is suggested to look over the standards catalog to establish its necessity, considering potential applications as: bioremediation for polluted water and soil, human health benefits (products with antioxidant activity) and farming and cattle advantages (natural plant growth stimulant and livestock feed). This paper provides a Sargassum spp. biomass composition (elements, isotopic) baseline data to complement adequate management strategies, possible valorization routes, development of regulatory measures, and biomonitoring programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

O. Zamora-Martínez, M. Monroy-Barreto, F.E. Mercader Trejo, R. Herrera Basurto, J.C. Aguilar-Cordero, I. Zaldívar-Coria, I.P. Bernal-España, A.G. Gómez –Carrasco, E.D. Delgadillo-Mendoza, Ma. F. Leyvas-Acosta, A. Acosta-Huerta, C. Flores-Ávila, M.R. Covarrubias-Herrera, M.E. Núñez Gaytán, A.M Núñez-Gaytán, J.J. Recillas-Mota, A.P. Peña Álvarez, E. Rodríguez de S.M., S.C. Gama González, O.U. Rodríguez-Pacheco, M.A. Saavedra Pérez, M.A. Gómez Reali. and Project DGAPA-UNAM PE201324.

REFERENCES

Addico, G.N.D., & K.A.A. deGraft-Johnson. 2016. Preliminary investigation into the chemical composition of the invasive Brown seaweed Sargassum along the West Coast of Ghana. African Journal of Biotechnology 15: 2184-2191. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2015.15177.

Ajith, S., G. Rojith, P.U. Zacharia, R. Nikki, V.H. Sajna, V.B. Liya, & G. Grinson. 2019. Production, Characterization and Observation of Higher Carbon in Sargassum wightii Biochar From Indian Coastal Waters. Journal of Coastal Research 86: 193-197. https://doi.org/10.2112/si86-029.1.

Alkan, N., A. Alkan, A. Demiral, & M. Bahloul. 2020. Metals/metalloid in marine sediments, bioaccumulating in macroalgae and a mussel. Soil and Sediment Contamination 29: 569-594. https://doi.org/10.1080/15320383.2020.1751061.

Álvarez-Viñas, M., N. Flórez-Fernández, M.J. González-Muñoz, & H. Domínguez. 2019. Influence of molecular weight on the properties of Sargassum muticum fucoidan. Algal Research 38: 101393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2018.101393.

Alzate-Gaviria, L., J. Domínguez-Maldonado, R. Chablé-Villacis, E. Olguín-Maciel, R.M. Leal-Bautista, G. Canché-Escamilla, A. Caballero-Vázquez, C. Hernández-Zepeda, F.A. Barredo-Pool, & R. Tapia-Tussell. 2021. Presence of polyphenols complex aromatic “Lignin” in Sargassum spp. from Mexican Caribbean. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 9: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9010006.

Baker, P., U. Minzlaff, A. Schoenle, E. Schwabe, M. Hohlfeld, A. Jeuck, N. Brenke, D. Prausse, M. Rothenbeck, A. Brix, I. Frutos, K.M. Jörger, T.P. Neusser, R. Koppelmann, C. Devey, A. Brandt, & H. Arndt. 2018. Potential contribution of surface-dwelling Sargassum algae to deep-sea ecosystems in the southern North Atlantic. Deep-Sea Research Part II 148: 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2017.10.002.

Balboa, E.M., C. Gallego-Fábrega, A. Moure, & H. Domínguez. 2016. Study of the seasonal variation on proximate composition of oven-dried Sargassum biomass collected in Vigo Ria, Spain. Journal of Applied Phycology 28: 1943-1953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-015-0727-x.

Barbarino, E. & S.O. Lourenço. 2005. An evaluation of methods for extraction and quantification of protein from marine macro- and microalgae. Journal of Applied Phycology 17: 447-460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-005-1641-4.

Barstow, S.F. 1983. The ecology of Langmuir circulation: A review. Marine Environmental Research 9: 211-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/0141-1136(83)90040-5.

Bekah, D., A.D. Thakoor, A. Ramanjooloo, I. Chummun Phul, S. Botte, P. Roy, P. Oogarah, S. Curpen, N. Goonoo, J. Bolton, & A. Bhaw-Luximon. 2023. Vitamins, minerals and heavy metals profiling of seaweeds from Mauritius and Rodrigues for food security. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 115: 104909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104909.

Carrillo, S., A. Bahena, M. Casas, M.E. Carranco, C.C. Calvo, E. Ávila & F. Pérez-Gil. 2012. El alga Sargassum spp. como alternativa para reducir el contenido de colesterol en el huevo. Revista Cubana de Ciencia Agrícola 46: 181-186. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=193024447011.

Carrillo Domínguez, S., M. Casas-Valdez, F. Ramos Ramos, F. Pérez-Gil & I. Sánchez-Rodríguez. 2002. Algas marinas de Baja California Sur, México: Valor nutrimental. Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición 52: 400-405. http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-06222002000400012.

Casas-Valdez, M, H. Hernández-Contreras, A. Marín-Álvarez & R.N. Aguila-Ramírez. 2006. El alga marina Sargassum (Sargassaceae) una alternativa tropical para la alimentación de ganado caprino. Revista de Biología Tropical 54: 83-92. https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-77442006000100010.

Castellanos Ruelas, A.F., F. Cauich Huchim, L.A. Chel Guerrero, J.G. & Rosado Rubio. 2010. Vegetación marina en la elaboración de bloques multinutritivos para la alimentación de rumiantes. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias 1: 75-83. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-11242010000100007.

Chan, J.C.C., P.C.K. Cheung, & P.O. Ang Jr. 1997. Comparative studies on the effect of three drying methods on the nutritional composition of seaweed Sargassum hemiphyllum (Turn.) C.Ag. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 45: 3056-3059. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf9701749.

Chapman, P.M. 2007. Determining when contamination is pollution-Weight of evidence determinations for sediments and effluents. Environment International 33: 492-501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2006.09.001.

Centre d'Étude et de Valorisation des Algues, CEVA. 2020. Edible seaweed and microalga-Regulatory status in France and Europe. 2019 Update. CEVA, France. https://www.ceva-algues.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CEVA-Edible-algae-FR-and-EU-regulatory-update-2019.pdf.

Choi, Y.Y., S.J. Lee, H.S. Kim, J.K. Eom, D.H. Kim, & S.S. Lee. 2020. The potential nutritive value of Sargassum fulvellum as a feed ingredient for ruminants. Algal Research 45: 101761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2019.101761.

Chung, K. & Lee, J.A. 1989. The Effects of Heavy Metals in Seaweeds. The Korean Journal of Phycology 4: 221-238. https://www.e-algae.org/upload/pdf/algae-1989-4-2-221.pdf.

Circuncisão, A.R., M.D. Catarino, S.M. Cardoso, & A.M.S. Silva. 2018. Minerals from macroalgae origin: Health benefits and risks for consumers. Marine Drugs 16: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/md16110400.

Corales-Ultra, O.G., R.P. Peja Jr., & E.V. Casas Jr. 2019. Baseline study on the levels of heavy metals in seawater and macroalgae near an abandoned mine in Manicani, Guiuan, Eastern Samar, Philippines. Marine Pollution Bulletin 149: 110549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110549.

Davis, D., R. Simister, S. Campbell, M. Marston, S. Bose, S.J. McQueen-Mason, L.D. Gómez, W.A. Gallimore, & T. Tonon. 2021. Biomass composition of the golden tide pelagic seaweeds Sargassum fluitans and S. natans (morphotypes I and VIII) to inform valorisation pathways. Science of the Total Environment 762: 143134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143134.

Delgadillo Mendoza, E.D. 2022. Sargazo: fertilizante natural, alternativa sustentable. Tesis de Licenciatura, Facultad de Química, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. http://132.248.9.195/ptd2022/noviembre/0830452/Index.html.

Dewi, E.N., L. Rianingsih, & A.D. Anggo. 2019. The addition of different starters on characteristics Sargassum sp. Liquid fertilizer. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 246: 012045. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/246/1/012045.

Di Filippo Herrera, D.H. 2018. Actividad bioestimulante de extractos de macroalgas y su evaluación sobre el crecimiento de frijol mungo (Vigna radiata). Tesis Doctoral, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México. https://delfin.cicimar.ipn.mx/Biblioteca/busqueda/Tesis/944?Origen=coleccion_tesis.

Dirección General de Bibliotecas, DGB. 2023. Biblioteca Digital UNAM. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. https://www.dgb.unam.mx/.

Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance, DCNA. 2019. Prevention and clean-up of Sargassum in the Dutch Caribbean. Holanda. https://dcnanature.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/DCNA-Sargassum-Brief.pdf.

Fernández, F., C.J. Boluda, J. Olivera, L.A. Guillermo, B. Gómez, E. Echavarría & G.A. Mendis. 2017. Análisis elemental prospectivo de la biomasa algal acumulada en las costas de la República Dominicana durante 2015. Revista Centro Azúcar 44: 11-22. http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/caz/v44n1/caz02117.pdf.

Fleurence, J. & I. Levine, I. 2016. Seaweed in Health and Disease Prevention. 1a ed. Ed. Elsevier Inc., USA. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2014-0-02206-X.

García Salgado, S. 2013. Estudios de especiación de arsénico y acumulación de metales en muestras de interés medioambiental. Tesis Doctoral, Escuela Universitaria de Ingeniería Técnica de Obras Públicas, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, España. https://oa.upm.es/15311/1/SARA_GARCIA_SALGADO.pdf.

Gobert, T., A. Gautier, S. Connan, M.L. Rouget, T. Thibaut, V. Stiger-Pouvreau, & M. Waeles. 2022. Trace metal content from holopelagic Sargassum spp. Sampled in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean: Emphasis on spatial variation of arsenic and phosphorus. Chemosphere 308: 136186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136186.

Gojon Báez, H.H., D.A. Siqueiros Beltrones & H. Hernández Contreras. 1998. Digestibilidad ruminal y degradabilidad In Situ de Macrocystis pyrifera y Sargassum spp. en ganado bovino. Ciencias Marinas 24: 463-481. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=48024406.

Google Earth. 2024. Version 9.185.0.0. Google LLC IT Corporation, USA. https://www.google.com/earth/about/.

Gorham, J. & S.A. Lewey. 1984. Seasonal changes in the chemical composition of Sargassum muticum. Marine Biology 80: 103-107. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00393133.

Gouvêa, L.P., J. Assis, C.F.D. Gurgel, E.A. Serrão, T.C.L. Silveira, R. Santos, C.M. Duarte, L.M.C. Peres, V.F. Carvalho, M. Batista, E. Bastos, M.N. Sissini, & P.A. Horta, 2020. Golden carbon of Sargassum forests revealed as an opportunity for climate change mitigation. Science of the Total Environment 729, 138745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138745.

Gutiérrez Sánchez, C. 2023. Sargazo: de especie invasiva hacia una alternativa nutracéutica. Tesis de Licenciatura, Facultad de Química, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. http://132.248.9.195/ptd2023/septiembre/0847316/Index.html.

Håkanson, L. 1980. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control. A sedimentological approach. Water Research 14: 975-1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1354(80)90143-8.

Hernández López, F. 2014. Obtención de biogás a partir de algas del tipo Sargassum de la Playa Miramar de Cd. Madero, Tamaulipas. Tesis de Maestría en Energías Renovables, Centro de Investigación en Materiales Avanzados, S.C.-UUTT, México. https://repositorioslatinoamericanos.uchile.cl/handle/2250/2259738.

Hinds, C., H. Oxenford, J. Cumberbatch, F. Fardin, E. Doyle, & A. Cashman. 2016. Golden Tides: Management Best Practices for Influxes of Sargassum in the Caribbean with a Focus on Clean-up. Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES), The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados. https://doi.org/10.25607/obp-786.

Hou, X. 1999. Study on chemical species of inorganic elements in some marine algae by neutron activation analysis combined with chemical and biochemical separation techniques. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 242: 49-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02345894.

Hou, X. & X. Yan. 1998. Study on the concentration and seasonal variation of inorganic elements in 35 species of marine algae. The Science of the Total Environment 222: 141-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00299-X.

Huang, Z., R. Bi, S. Musil, A.H. Pétursdóttir, B. Luo, P. Zhao, X. Tan, & Y. Jia. 2022. Arsenic species and their health risks in edible seaweeds collected along the Chines coastline. Science of the Total Environment 847: 157429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157429.

Ismail, G.A. 2017. Biochemical composition of some Egyptian seaweeds with potent nutritive and antioxidant properties. Food Science and Technology 37: 294-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1678-457X.20316.

Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático, INECC 2021. Lineamientos Técnicos y de Gestión para la Atención de la Contingencia Ocasionada por Sargazo en el Caribe Mexicano y el Golfo de México. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, SEMARNAT. México

https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/636709/SEMARNAT-INECC-SARGAZO-2021.pdf.

Kannan, S. 2014. FT-IR and EDS analysis of the seaweeds Sargassum wightii (brown algae) and Gracilaria corticata (red algae). International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 3: 341-351. https://ijcmas.com/vol-3-4/S.Kannan.pdf.

Karimian, S., S. Shekoohiyan, & G. Moussavi. 2021. Health and ecological risk assessment and simulation of heavy metal-contaminated soil of Tehran landfill. RSC Advances 11:8080. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ra08833a.

Kaviarasan, T., M.S. Gokul, S. Henclya, K. Muthukumar, H.U. Dahms, & R.A. James. 2018. Trace metal inference on seaweeds in Wandoor Area, Southern Andaman Island. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 100: 614-619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-018-2305-9.

Khristoforova, N.K. & S.I. Kozhenkova. 2002. The use of brown algae Sargassum spp. in heavy metal monitoring of the marine environment near Vladivostok, Russia. Ocean and Polar Research 24: 325-329. https://doi.org/10.4217/OPR.2002.24.4.325.

Kordjazi, M., Y. Etemadian, B. Shabanpour, & P. Pourashouri. 2019. Chemical composition antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of fucoidan extracted from two species of brown seaweeds (Sargassum ilicifolium and S. angustifolium) around Qeshm Island. Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences 18: 457-475. https://jifro.ir/browse.php?a_id=2659&sid=1&slc_lang=en.

Kuda, T. & T. Ikemori. 2009. Minerals, polysaccharides and antioxidant properties of aqueous solutions obtained from macroalgal beach-casts in the Noto Peninsula, Ishikawa, Japan. Food Chemistry 112: 575-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.06.008.

Kumar, S. & D. Sahoo. 2017. A comprehensive analysis of alginate content and biochemical composition of leftover pulp from Brown seaweed Sargassum wightii. Algal Research 23: 233-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2017.02.003.

Kumar, S., D. Sahoo, & I. Levine. 2015. Assessment of nutritional value in a brown seaweed Sargassum wightii and their seasonal variations. Algal Research 9: 117-125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2015.02.024.

Kumari, R., I. Kaur, & A.K. Bhatnagar. 2013. Enhancing soil health and productivity of Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. using Sargassum johnstonii Setchell & Gardner as a soil conditioner and fertilizer. Journal of Applied Phycology 25: 1225-1235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-012-9933-y.

Leyvas Acosta, M.F., MT.J. Rodríguez Salazar & M. Monroy Barreto. 2023. Sargazo y biosorción (investigación documental preliminar 2016-2022). Memorias del 3er Congreso Internacional de Educación Química 2022, Sociedad Química de México, México: 166-171. https://sqm.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Memorias-3%C2%B0CIEQ.pdf.

Li, W., Y. Zhang, J. Zhang, H. Chen, E. Chen, L. Zhao, & D. Zhao. 2023. Tropical forest AGB estimation based on structure parameters extracted by TomoSAR. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 121: 103369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103369.

Lourenço, R.A., C.A. Magalhães, S. Taniguchi, S.G. Leite Siqueira, G. Buz Jacobucci, F.P. Pereira Leite, & M. Caruso Bícego. 2019. Evaluation of macroalgae and amphipods as bioindicators of petroleum hydrocarbons input into the marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 145: 564-568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.05.052.

Madkour, A.G., S.H. Rashedey, & M.A. Dar. 2019. Spatial and temporal variation of heavy metals accumulation in some macroalgal flora of the Red Sea. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries 23: 539-549. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejabf.2019.60548.

Magura, J., R. Moodley, & S.B. Jonnalagadda. 2019. Toxic metals (As and Pb) in Sargassum elegans Suhr (1840) and the bioactive compounds. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 29: 266-273. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2018.1537439.

Magura, J., R. Moodley, & S.B. Jonnalagadda. 2016. Chemical composition of selected seaweeds from the Indian Ocean, KwaZulu-Natal coast, South Africa. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B 51: 525-533. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601234.2016.1170547.

Mahammad Diganta, M.T., A.S.M. Saifullah, M.A. Bakar Siddique, M. Mostafa, M.S. Sheikh, & M.J. Uddin. 2023. Macroalgae for biomonitoring of trace elements in relation to environmental parameters and seasonality in a sub-tropical mangrove estuary. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 256: 104190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2023.104190.

Mahmoud, S.H., D.M. Salama, A.M.M. El-Tanahy, & E.H.A. El-Samad. 2019. Utilization of seaweed (Sargassum vulgare) extract to enhance growth, yield and nutritional quality of red radish plants. Annals of Agricultural Sciences 64: 167-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aoas.2019.11.002.

Marinho-Soriano, E., P.C. Fonseca, M.A.A. Carneiro, & W.S.C. Moreira. 2006. Seasonal variation in the chemical composition of two tropical seaweeds. Bioresource Technology 97: 2402-2406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.10.014.

Martínez-Rodríguez, L.I. 2020. Composición de isótopos estables de carbono y nitrógeno en especies pelágicas de sargazo. Tesis de Maestría (Uso, Manejo y Preservación de los Recursos Naturales, Orientación en Biología Marina), Posgrado, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noreste, S.C., México. http://dspace.cibnor.mx:8080/handle/123456789/3069.

Marzocchi, M., D. Radocco, A. Piovan, P. Pastore, V. Di Marco, R. Filippini, & R. Caniato. 2016. Metals in Undaria pinnatifida (Harvey) Suringar and Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt edible seaweeds growing around Venice (Italy). Journal of Applied Phycology 28: 2605-2613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-016-0793-8.

Matanjun, P., S. Mohamed, N.M. Mustapha, & K. Muhammad. 2009. Nutrient content of tropical edible seaweeds, Euchema cottonii, Caulerpa lentillifera and Sargassum polycystum. Journal of Applied Phycology 21: 75-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-008-9326-4.

McDermid, K.J. & B. Stuercke. 2003. Nutritional composition of edible Hawaiian seaweeds. Journal of Applied Phycology 15: 513-524. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JAPH.0000004345.31686.7f.

Milledge, J.J. & P. Harvey. 2016. Ensilage and anaerobic digestion of Sargassum muticum. Journal of Applied Phycology 28: 30213030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-016-0804-9.

Milledge, J.J., A. Staple, & P.J. Harvey. 2015. Slow pyrolysis as a method for the destruction of Japanese wireweed, Sargassum muticum. Environmental and Natural Resources Research 5: 28-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v5n1p28.

Mišurcová, L., I. Stratilová, & S. Kráčmar. 2009. Obsah minerálních látek ve vybraných produktechz mořských a sladkovodních řas. Chem. Listy 103: 1027-1033. https://adoc.pub/laboratorni-pistroje-a-postupy96bed53b199d0206eea9bbdb59fd252658905.html.

Murugaiyan, K. & S. Narasimman. 2012. Elemental composition of Sargassum longifolium and Turbinaria conoides from Pamban Coast, Tamilnadu. International Journal of Research in Biological Sciences 2: 137-140. https://www.academia.edu/90866290.

Ortega-Flores, P.A., E. Serviere-Zaragoza, J.A. De Anda-Montañez, Y. Freile-Pelegrín, D. Robledo, & L.C. Méndez-Rodríguez. 2022. Trace elements in pelagic Sargassum species in the Mexican Caribbean: Identification of key variables affecting arsenic accumulation in S. fluitans. Science of the Total Environment 806: 150657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150657.

Oyesiku, O.O. & A. Egunyomi. 2014. Identification and chemical studies of pelagic masses of Sargassum natans (Linnaeus) Gaillon and S. fluitans (Borgessen) Borgesen (brown algae), found offshore in Ondo State, Nigeria. African Journal of Biotechnology 13: 11881193. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2013.12335.

Peng, Y., E. Xie, K. Zheng, M. Fredimoses, X. Yang, X. Zhou, Y. Wang, B. Yang, X. Lin, J. Liu, & Y. Liu. 2013. Nutritional and chemical composition and antiviral activity of cultivated seaweed Sargassum naozhouense Tseng et Lu. Marine Drugs 11: 20-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11010020.

Praiboon, J., S. Palakas, T. Notraksa, & K. Miyashita. 2018. Seasonal variation in nutritional composition and anti-proliferative activity of brown seaweed Sargassum oligocystum. Journal of Applied Phycology 30: 101-111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-017-1248-6.

Puspita, M. 2017. Enzyme-assisted extraction of phlorotannins from Sargassum and biological activities. Doctoral Program. Medicinal Chemistry. Diponegoro University, Université Bretagne Sud. https://hal.science/tel-01630154v1/document.

Rahhou, A., M. Layachi, M. Akodad, N. El Ouamari, A. Aknaf, A. Skalli, B. Oudra, M. Kolar, J. Imperl, P. Petrova, & M. Baghour. 2023. Analysis and health risk assessment of heavy metals in four common seaweeds of Marchica lagoon (a restores lagoon, Moroccan Mediterranean). Arabian Journal of Chemistry 16: 105281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105281.

Rajaram, R., S. Rameshkumar, & A. Anandkumar. 2020. Health risk assessment and potentiality of green seaweeds on bioaccumulation of trace elements along the Palk Bay coast, Southeastern India. Marine Pollution Bulletin 154: 111069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111069.

Rakib, M.R.J., Y.N. Jolly, D.C. Dioses-Salinas, C.I. Pizarro-Ortega, G.E. De-la-Torre, M.U. Khandaker, A. Alsubaie, A.S.A. Almaki, & D.A. Bradley. 2021. Macroalgae in biomonitoring of metal pollution in the Bay of Bengal coastal waters of Cox´s Bazar and surrounding areas. Scientific Reports 11: 20999. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99750-7.

Ramírez Cruz, J.I. 2021. Arsénico en algas cafés del género Sargassum: condiciones empleadas para su remoción del agua. Tesis de Maestría. Uso, Manejo y Preservación de los Recursos Naturales (Orientación en Biología Marina), Posgrado, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S.C., México. http://dspace.cibnor.mx:8080/handle/123456789/3130.

Rodrigues, D., A.R. Costa-Pinto, S. Sousa, M.W. Vasconcelos, M.M. Pintado, L. Pereira, T.A.P. Rocha-Santos, J.P. da Costa, A.M.S. Silva, A.C. Duarte, A.M.P. Gomes, & A.C. Freitas A.C. 2019. Sargassum muticum and Osmundea pinnatifida enzymatic extracts: Chemical, structural, and cytotoxic characterization. Marine Drugs 17: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17040209.

Rodrigues, D., A.C. Freitas, L. Pereira, T.A.P. Rocha-Santos, M.W. Vasconcelos, M. Roriz, L.M. Rodríguez-Alcalá, A.M.P. Gomes, & A.C. Duarte. 2015. Chemical composition of red, brown and green macroalgae from Buarcos bay in Central West Coast of Portugal. Food Chemistry 183: 197-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.057.

Rodríguez Bernal, M.G. 1995. Las algas marinas Sargassum sinicola y Ulva lactuca como fuentes alternas de minerales y pigmentos en gallinas de postura. Tesis de Maestría (Producción Animal), División de Estudios de Posgrado e Investigación, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. http://132.248.9.195/pmig2016/0221130/Index.html.

Rodriguez-Martínez, R.E., P.D. Roy, N. Torrescano-Valle, N. Cabanillas-Terán, S. Carrillo-Domínguez, L. Collado-Vides, M. García-Sánchez, & B.I. van Tussenbroek. 2020. Element concentrations in pelagic Sargassum along the Mexican Caribbean coast in 2018-2019. PeerJ 8:e8667: 1-19. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8667.

Rodríguez Salazar, M.T.J., F.E. Mercader Trejo, M. Monroy Barreto, R. Herrera Basurto, A. Skladal Méndez, A.J. Morales Velázquez, A.G. Gómez Carrasco, C. Gutiérrez Sánchez, E.D. Delgadillo Mendoza, E.E. Mendoza Solís, I.P. Bernal España, & M.F. Leyvas-Acosta. 2023. Base de datos (1984-2022) de composición química de sargazo: Análisis elemental. Memorias del Congreso Internacional de la Sociedad Química de México 2022, Sociedad Química de México, México: 21-31. https://sqm.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Memorias-CISQM2022.pdf.

Rohani-Ghadlkolact, K., E. Abdulalian, & W.K. Ng. 2012. Evaluation of the proximate, fatty acid and mineral composition of representative green, brown and red seaweeds from the Persian Gulf of Iran as potential food and feed resources. Journal of Food Science Technology 49: 774-780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-010-0220-0.

Rushdi, M.I., I.A.M. Abdel-Rahman, H. Saber, E.Z. Attia, W.M. Abdelraheem, H.A. Madkour, H.M. Hassan, A.H. Elmaidomy, & U.R. Abdelmohsen. 2020. Pharmacological and natural products diversity of the Brown algae genus Sargassum. RSC Advances 10: 24951-24972. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0RA03576A.

Santoso, J., S. Gunji, Y. Yoshie-Stark, & T. Suzuki. 2006. Mineral contents of Indonesian seaweeds and mineral solubility affected by basic cooking. Food Science Technology Research 12: 59-66. https://doi.org/10.3136/fstr.12.59.

Secretaría de Economía, SE & Secretaría de Salud, SSA 2010. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010, Especificaciones generales de etiquetado para alimentos y bebidas no alcohólicas preenvasados-Información comercial y sanitaria. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/4010/seeco11_C/seeco11_C.htm.

Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, 2002. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-021-RECNAT-2000, Que establece las especificaciones de fertilidad, salinidad y clasificación de suelos. Estudios, muestreo y análisis. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=717582&fecha=31/12/2002#gsc.tab=0.

Secretaría de Planeación e Informática, SPI 2023. Administrador de Manuales y Documentos. Facultad de Química, UNAM, México. https://amyd.quimica.unam.mx/course/view.php?id=662§ion=5.

Seepersaud, M., A. Ramkissoon, S. Seecharan, Y.L. Powder-George, & F.K. Mohammed. 2018. Environmental monitoring of heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Sargassum filipendula and Sargassum vulgare along the Eastern coastal waters of Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies. Journal of Applied Phycology 30: 2143-2154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-017-1372-3.

SEMARNAT 2003. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-004-SEMARNAT-2002, Protección ambiental - Lodos y biosólidos.-Especificaciones y límites máximos permisibles de contaminantes para su aprovechamiento y disposición final. Diario Oficial de la Federación. México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=691939&fecha=15/08/2003#gsc.tab=0.

SEMARNAT, SS 2007. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-147-SEMARNAT/SSA1-2004, Que establece criterios para determinar las concentraciones de remediación de suelos contaminados por arsénico, bario, berilio, cadmio, cromo hexavalente, mercurio, níquel, plata, plomo, selenio, talio y/o vanadio. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4964569&fecha=02/03/2007#gsc.tab=0.

Shams El-Din, N.G., L.I. Mohamedein, & Kh.M. El-Moselhy. 2014. Seaweeds as bioindicators of heavy metals off a hot spot area on the Egyptian Mediterranean Coast during 2008-2010. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 186: 5865-5881. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10661-014-3825-3.

Siddique, M.A.M., Md. Sh. Hossain, Md. M. Islam, M. Rahman, & G. Kibria. 2022. Heavy metals and metalloids in edible seaweeds of Saint Martin´s Island Bay of Bengal, and their potential health risks. Marine Pollution Bulletin 181: 113866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113866.

Solarin, B.B., D.A. Bolaji, O.S. Fakayode, & R.O. Akinnigbagbe. 2014. Impacts of an invasive seaweed Sargassum hystrix var. fluitans (Borgesen 1914) on the fisheries and other economic implications for the Nigerian coastal waters. IOSR Journal of Agricultural and Veterinary Science 7: 01-06. https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-javs/papers/vol7-issue7/Version-1/A07710106.pdf.

Soto, M., M.A. Vázquez, A. de Vega, J.M. Vilariño, G. Fernández, & M.E.S. de Vicente. 2015. Methane potential and anaerobic treatment feasibility of Sargassum muticum. Bioresource Technology 189: 53-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.03.074.

SSA 2010. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-242-SSA1-2009, Productos y servicios. Productos de la pesca frescos, refrigerados, congelados y procesados. Especificaciones sanitarias y métodos de prueba, Diario Oficial de la Federación. México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/4295/salud2a/salud2a.htm.

SSA 2009. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-247-SSA1-2008, Productos y servicios. Cereales y sus productos. Cereales, harinas de cereales, sémolas o semolinas. Alimentos a base de: cereales, semillas comestibles, de harinas, sémolas o semolinas o sus mezclas. Productos de panificación. Disposiciones y especificaciones sanitarias y nutrimentales. Métodos de prueba. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México. https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5100356&fecha=27/07/2009#gsc.tab=0.

SSA, SE 2003. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-187-SSA1/SCFI-2002, Productos y servicios. Masa, tortillas, tostadas y harinas preparadas para su elaboración y establecimientos donde se procesan. Especificaciones sanitarias. Información comercial. Métodos de prueba. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=691995&fecha=18/08/2003#gsc.tab=0.

SS 2022. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-127-SSA1-2021, Agua para uso y consumo humano. Límites permisibles de la calidad del agua. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5650705&fecha=02/05/2022#gsc.tab=0.

Su, L., W. Shi, X. Chen, L. Meng, L. Yuan, X. Chen, & G. Huang. 2021. Simultaneously and quantitatively analyze the heavy metals in Sargassum fusiforme by laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Food Chemistry 338 (127797): 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127797.

Sumandiarsa, I.K., D.G. Bengen, J. Santoso, & H.I. Januar. 2020. Nutritional composition and alginate characteristics of Sargassum polycystum (C. Agardh, 1824) growth in Sebesi island coastal, Lampung-Indonesia. IOP Conf Series: Earth and Environmental Science 584: 012016. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/584/1/012016.

Sutharsan, S., S. Nishanthi, & S. Srikrishnah. 2014. Effects of foliar application of seaweed (Sargassum crassifolium) liquid extract on the performance of Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. in sandy regosol of Batticaloa District Sri Lanka. American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences 14: 1386-1396. https://www.idosi.org/aejaes/jaes14(12)14/9.pdf.

Syad, A.N., K.P. Shunmugiah, & P.D. Kasi. 2013. Seaweed as nutritional supplements: Analysis of nutritional profile physicochemical properties and proximate composition of G. acerosa and S. wightii. Biomedicine & Preventive Nutrition 3: 139-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bionut.2012.12.002.

Tamura, M., Y. Suzuki, H. Akiyama, & N. Hamada-Sato. 2022. Evaluation of the effect of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus SN001 fermentation on arsenic accumulation and antihypertensive effect of Sargassum horneri in vivo. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 395: 1549–1556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-022-02288-2.

Thadhani, V.M., A. Lobeer, W. Zhang, M. Irfath, P. Su, N. Edirisinghe, & G. Amaratunga. 2019. Comparative analysis of sugar and mineral content of Sargassum spp. collected from different coasts of Sri Lanka. Journal of Applied Phycology 31: 2643–2651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-01770-4.

Thompson, T.M., B.R. Young, & S. Baroutian. 2020. Efficiency of hydrothermal pretreatment on the anaerobic digestion of pelagic Sargassum for biogas and fertiliser recovery. Fuel 279: 118527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118527.

Timoner Alonso, I., J. Bosch Collet, V. Castell Garralda, S. Abulin, & J. Calderón. 2020. Algues. Estudi de la presència de metalls pesants i iode en algues destinades al consum humà. Avaluació del risc associat i la seva contribució a la dieta total. Agència Catalana de Seguretat Alimentària, Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Salut, España. https://scientiasalut.gencat.cat/handle/11351/5376?locale-attribute=en.

Torres, M.D., N. Flórez-Fernández, & H. Domínguez. 2021. Monitoring of the ultrasound assisted depolymerisation kinetics of fucoidans from Sargassum muticum depending of the rheology of the corresponding gels. Journal of Food Engineering 294 (110404): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2020.110404.

Tyovenda, A.A., S.I. Ikpughul, & T. Sombo. 2019. Assessment of heavy metal pollution of water, sediments and algae in River Benue at Jimeta-Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria. Nigerian Annals of Pure and Applied Sciences 1:186-195. https://doi.org/10.46912/napas.44.

Uddin, S., M. Bebhehani, S. Sajid & Q. Karam. 2019. Concentration of 210Po and 210Pb in macroalgae from the northern Gulf. Marine Pollution Bulletin 145: 474-479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.06.056.

Uribe-Orozco, M.E., L.E. Mateo-Cid, A.C. Mendoza-González, E.F. Amora-Lazcano, D. Gónzalez-Mendoza & D. Durán-Hernández. 2018. Efecto del alga marina Sargassum vulgare C. Agardh en suelo y el desarrollo de plantas de cilantro. IDESIA 36: 69-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34292018005001202.

Vázquez-Delfín, E., Y. Freile-Pelegrín, A. Salazar-Garibay, E. Serviere-Zaragoza, L.C. Méndez-Rodríguez, & D. Robledo. 2021. Species composition and chemical characterization of Sargassum influx at six different locations along the Mexican Caribbean coast. Science of the Total Environment 795: 148852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148852.

Vijayanand, N., S. Ramya, & S. Rathinavel. 2014. Potential of liquid extracts of Sargassum wightii on growth, biochemical and yield parameters of cluster bean plant. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction 3: 150-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2305-0500(14)60019-1.

Wernberg, T., M.S. Thomsen, P.A. Stæhr & M.F. Pedersen. 2000. Comparative phenology of Sargassum muticum and Halidrys siliquosa (Phaeophyceae: Fucales) in Limfjorden, Denmark. Botanica Marina 43, 31-39. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2001.005.

Yoganandham, S.T., V. Raguraman, G. Muniswamy, G. Sathyamoorthy, R.R. Renuka, J. Chidambaram, T. Rajendran, K. Chandrasekaran, & R.R.S. Ravindranath. 2019. Mineral and trace metal concentrations in seaweeds by microwave-assisted digestion method followed by Quadrupole Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. Biological Trace Element Research 187: 579-585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-018-1397-8.

Yu, Z., S.M.C. Robinson, J. Xia, H. Sun, & C. Hu. 2016. Growth, bioaccumulation and fodder potentials of the seaweed Sargassum hemiphyllum grown in oyster and fish farms of South China. Aquaculture 464, 459-468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.07.031.

Zeng, G.Z., S. Lou, H. Ying, X. Wu, X. Dou, N. Ai & J. Wang. 2018. Preparation of microporous carbon from Sargassum horneri by hydrothermal carbonization and KOH activation for CO2 capture. Journal of Chemistry 4319149:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4319149.

Zheng, X., R. Sun, Z. Dai, L. He, & Ch. Li. 2023. Distribution and risk assessment of microplastics in typical ecosystems in the South China Sea. Science of the Total Environment 883:163678. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163678.

Zubia, M., C.E. Payri, E. Deslandes, & J. Guezennec. 2003. Chemical composition of attached and drift specimens of Sargassum mangarevense and Turbinaria ornata (Phaeophyta: Fucales) from Tahiti, French Polynesia. Botanica Marina 46: 562-571. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2003.059.

Recibido: 15 de noviembre de 2024

Revisado: 4 de febrero de 2025

Corregido: 20 de febrero de 2025

Aceptado: 26 de febrero de 2025

Para ver las tablas descargue el PDF del Artículo aquí